National Food Security Standard (hereinafter referred to as the “National Standard”) is crucial to

anyone who works in the food industry. However, many people are not clear about the classification of

National Standard, which is important to foreign exporters.

Let’s start with the Food Safety Law, which is the

fundamental law of food safety. According to the Food

Safety Law, Chapter 3 Food Safety Standards, Article 25:

Food safety standards shall be standards for mandatory

execution. No mandatory food standards other than food

safety standards may be developed.

Article 26. Food safety standards shall contain:

✔ limits of pathogenic microorganisms, pesticide

residues, residues from veterinary medicines, biological

toxins, heavy metals, and other pollutants, and other

substances hazardous to human health in food, food

additives, and food-related products;

✔ varieties, range of application, and dosages of food

additives;

✔ nutritional composition requirements for staple and

supplementary food exclusively for infants and other

particular groups of people

✔ requirements for labels, marks, and instructions

related to health, nutrition, and other food safety

requirements;

✔ hygienic requirements for the process of food

production or trade;

✔ quality requirements related to food safety;

✔ food inspection methods and procedures related to

food safety; and

✔ others which need to be developed into food safety

standards.

Obviously, the upper rank law has provided a clear position

and scope for the national standard of food safety, so next

step we will explain in detail the specific classification of

national standards.

The first category is common criteria

Common criteria refer to standards that are widely used

and have broad guiding significance as the basis of other

standards within a certain range.

In another word, all food products, no matter what

category they belong to, shall comply with the common

criteria.

For example, if there is no corresponding food product

standard for a food product imported from abroad, you can

find the corresponding common criteria according to the

food category of the product and comply with the safety

requirements for the food category in the standard.

In this way, the national standard problem in food import

can be solved.

There are 13 common criteria as the list below:

Among the 13 general standards, the following standards

are most commonly used:

✓ General standard for the labelling of prepackaged

foods GB 7718-2011

✓ Standard for nutrition labelling of prepackaged

foods GB 28050-2011

✓ Standard for use of food additives GB 2760-2014

✓ Limits of contaminants in foods GB 2762-2017

✓ Limit of pathogen in prepackaged foods GB 29921-2021

Due to space reasons, the content of the standard will

not be explained in detail here. Readers can search about

the detailed standard and find the explanation by the

professional practitioners of food regulation in accordance

with specific situation.

It is hereby noted that clarified that the use of “most” and

other superlatives in this article is to impress the readers

and not the absolute words.

The second category is standard of food products

A total of 70 national standards are formulated for major

food categories (important to people's livelihood), such

as various dairy products, rice and flour products, meat

products, candy products, seasoning products, etc.

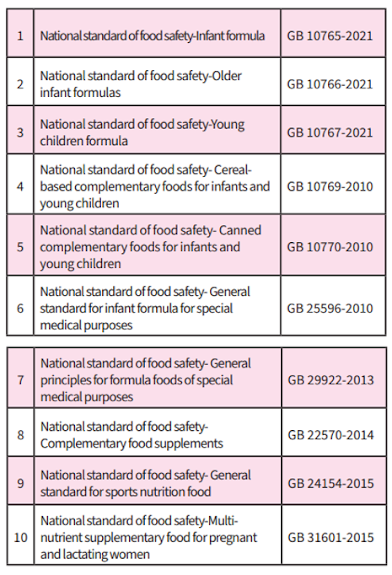

The third category is special dietary food standards,

which is used for specific consumer groups such as infant

formula and other special food. Relevant national standards

shall be abided by. There are 10 standards in total:

The fourth category is quality specifications and

relevant standards of food additives

This category has the most national standards, 646 in total.

All the food additives shall abide by this kind of standard,

which will not be listed here due to space reasons.

The fifth category is quality specification and standard

of food nutrition fortifier

There are 53 standards in total. All the food nutrition

fortifier shall abide by this kind of standard, which will not

be listed here due to space reasons.

The sixth category is food related product standards

There are 15 standards in total. Food related products

refer to food packaging materials, containers, detergents,

disinfectants, etc. and there are 3 important standards:

➤ detergent GB 14930.1-2015

➤ disinfectants GB 14930.2-2012

➤ General safety requirements on food contact

materials and articles GB 4806.1-2016

The seventh category is production and operation

specifications and standards

There are 34 standards in total, which shall be abided by

during the production and operation of the food. There are

two important standards:

➤ General hygienic standard for food production

GB 14881-2013

➤ Code of hygienic practice in food business process

GB 31621-2014

The remaining standards are various test methods,

including 234 physical and chemical test methods,

32 microbiological test methods, 29 toxicological test

methods and procedures, 120 pesticide residue test

methods and 74 veterinary drug residue test methods.

Conclusion

The above analysis is based on the announcement of

the Food Safety Standards Monitoring and Evaluation

Department of National Health Commission in February

2022, which is the latest official announcement.

It is hoped that the popularization of science will help

nonprofessionals of food regulation to have a preliminary

understanding of national standards of food safety.

Leon Zheng

Leon Zheng HFG Law&Intellectual Property